The geological formation and evolution of Fundy is but the first chapter of a long and extraordinary tale. It is a story which, by nature of the diverse characteristics of the Bay, has propagated an interconnected universe of dynamics: the highest and most powerful tides in world, a globally significant ecosystem, the largest concentration of whales and other sea-life, the single most important stopover point for migrating shorebirds along the entire Eastern Seaboard, a body of water that influences and modifies the weather, decrees the surrounding forests and foliage, and ultimately, sways the lives of those who live on her shores.

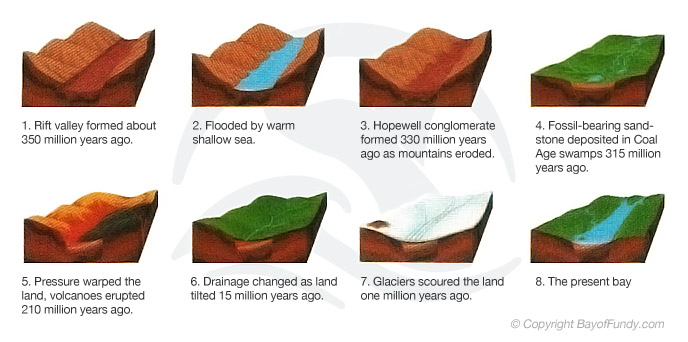

The genesis of this geological and ecological phenomenon occurred an estimated 350 million years ago (Burzynski and Marceau, 1984).

In an event of unimaginable scale and proportion, the continental plates of Africa and North America wrenched apart, forming the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantean plates ruptured along geological fault lines virtually parallel to the contemporary continental margins. And as vast mountain ranges collided and then slowly separated, huge rift valleys were created in their cleavage. Over time, these colossal depressions infilled with sediments from the surrounding mountains, and today, several major sedimentary basins have been located, but Fundy is the most northerly in the world (Thurston, 1994).

Internal Big Box]

Some 150 million years later, with the southern tip of what we now call Nova Scotia still firmly joined to what we now call the State of Maine, the Fundy basin became nothing more than a warm, shallow lake. However, with no replenishment of fresh water, large parts of the basin evaporated, leaving significant deposits of eroded sediments, including gypsum, salt and potash, which are still commonly found in the rocks and cliffs of the Bay of Fundy (Dolgoff, 1998). Thousands and thousands of millenniums later, the industrialized economies of the Maritimes came to depend on these deposits for extensive mining operations (Thurston, 1994).

As the basin became a parched and barren abyss, heavy rains flushed the mountains of thick reddish rubble and sand. Today’s spectacular towering flowerpot Hopewell Rocks are a consequence of this process (Burzynski and Marceau, 1984). And as the eons ticked by’, further geological gestation evolved when the earth’s crust around the basin heaved in a series of folds and faults. Thick deposits of sandstone and shale resulted from perpetual erosion, still visible today in the Minas Basin. And the basalt cliffs at Cap d’Or, Cape Split, Digby and Grand Manan are testimony to the volcanoes of molten rock and lava which spewed from subterranean depths.

The craggy escarpment which rings this immense gulf was formed during a critical juncture in Earth history called the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, 200 million years ago (Thurston, 1994). On the basis of the fossil record, paleontologists have determined that nearly half of the world’s creatures never made it across this threshold in time (Dolgoff, 1998). The world’s leading expert on the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, Dr. Paul Olsen of Columbia University, has found preserved in the rocks that enclose Fundy’s Minas Basin, the bones and footprints of the victims and survivors of this cataclysm. These fossils offer scientists the best chance of discovering what caused the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, and perhaps others like it, that have punctuated the evolution of our planet and determined the fate of its inhabitants – including man.

And almost as a spectacular finale to the opening act of creation (a mere 15 thousand years ago), following the last slowly receding Ice Age, the Atlantic Ocean rose to claim the great rift valley for it’s own (Burzynski and Marceau, 1984). In consequence, the sea waters would be radically affected by this uniquely shaped and symmetrically formed crater. For here, as in no other place on Earth, water and sphere would join in ceaseless concert to give birth to one of the great marine wonders of the world.

According to Dr. Olsen, the most promising locations in the quest for answers to our ancient past are on the tide-swept shores of the Bay of Fundy. For despite almost 400 years of North American settlement by the first Europeans (1604), Fundy is still considered one of the world’s most natural and unspoiled places.

Of all the basins on the planet, the sediments of Fundy are the most exposed, thanks to the erosive action of the Bay’s great tides. Their ebb and flow continues to open windows in time. And the story of the evolution may be read in the rocks, shale and basalt cliffs surrounding this massive estuary. The rocks serve as mute testimony to the volcanic action that intervened here, a mosaic of igneous and sedimentary stone, blended with the sands and eroded shingle, grit and gravel.

References:

- Pinet, P.R. 1998. Invitiation to Oceanography, web enhanced ed. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Boston, Ma.

- Burzynski, M. and Marceau, A. 1984. Fundy: Bay of the Giant Tides, 3rd ed. The Fundy Guild Publishing, Alma, New Brunswick.

- Cutnell, J. D. and Johnson. 1995. Physics, 3rd ed. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York

- Dolgoff, A. 1998. Physical Geology, Updated version. Houghton Mifflin Co. New York

- Randall, D., Burggren, W. and French, K, 1998. Animal Physiology: Mechanisms and Adaptations, 3rd ed. W.H. Freeman and Co. New York.

- Smith, R.L. and Smith, T.M. 1998. Elements of Ecology, 4th ed. Benjamin – Cummings Publishing Co. Menlo Park, Ca.

- Thurston, H. and Horner, S. 1998. Tidal Life. Nimbus. Toronto.

Talia

There’s an error in the text and the related graphic; I used this page as a source for a geology project and got points off because Africa and North America broke apart just 180 MYA, not 350 like it says.

oyuky

hey i would like to know if any of you have ideas for he geological issues of building a dam in the Bay of Fundy. My geology group in high school physics is trying to create a dam project. THANK YOU! please reply

David Quinn

Informative article, complete with citations! Makes me want to read more when I arrive and after I visit next week!